The Ultimate Guide to German Tenses

Learn how to use the different German tenses in the right situations.

I want to learn...

Using the right German tenses is an important part of language learning since you want to express what you are doing right now, what you did in the past, or what you will do in the future. It is one of the big grammar topics that needs to be learned in every language, but once you mastered it, you are ready for your time travels.

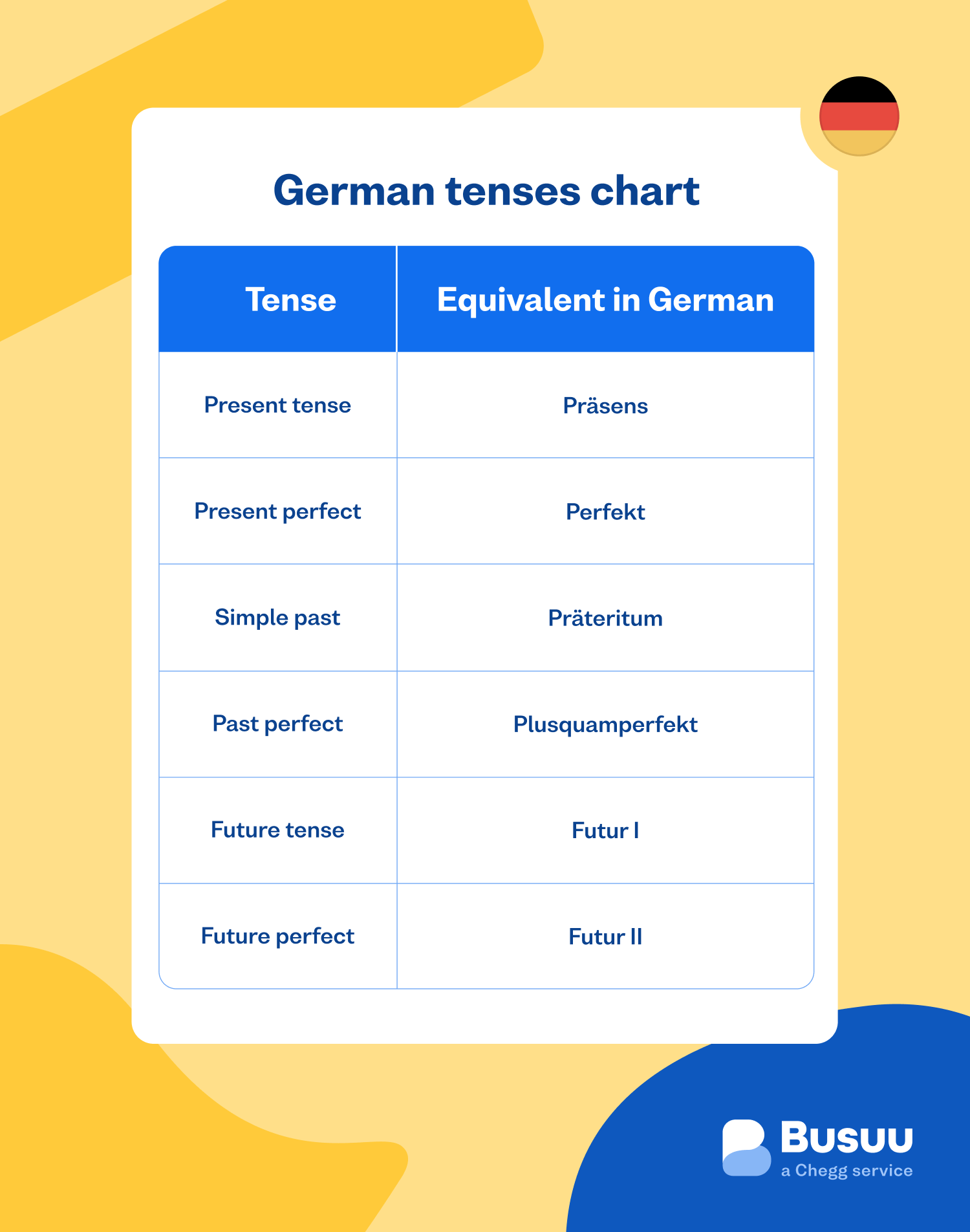

It may seem a bit overwhelming in the beginning since there is a lot to know about in which situations to use which tense in German. But there is no reason to sneak out of that. We have the ultimate guide for you to prepare for your travels. Before we dive into this linguistic journey in more detail, here is a little German tenses chart as an overview of which tenses in German exist:

German tenses chart

| Tense | Equivalent in German |

|---|---|

| Present tense | Präsens |

| Present perfect | Perfekt |

| Simple past | Präteritum |

| Past perfect | Plusquamperfekt |

| Future tense | Futur I |

| Future perfect | Futur II |

Let’s break them down one by one!

German present tense

The German present tense (Präsens) is similar in its function to the English present tense and used to express actions and happenings that are generally true or frequent, but also if they are happening right in the moment when you are saying it, or if they will happen in the future.

- Ich koche jeden Sonntag. (I cook every Sunday.)

- Ich koche (gerade). (I am cooking (right now).)

- Ich koche morgen für meine Familie. (I will cook for my family tomorrow.)

German tenses don’t have “progressive” forms (English: I am cooking). This makes it kind of easy since you would just use the present tense to express everything you are doing in the moment of speaking.

Before we can dive into any of the other tenses, let’s have a more extensive look at conjugation rules for the German present tense. In a nutshell, “conjugation” means adapting the verb to the person who’s performing the activity. Once you’ve mastered these fundamental rules, you’ll have laid the perfect foundation to learn all the other German tenses, and will soon be able to use them correctly when you are traveling to German-speaking countries.

Regular verbs in German

Let’s see how to conjugate regular verbs using the example of kommen (to come):

Conjugating the regular verb kommen

| Gernab | English |

|---|---|

| ich komme | I come / I am coming |

| du kommst | you come / you are coming |

| er/sie/es kommt | he/she/it comes / he/she/it is coming |

| wir kommen | we come / we are coming |

| ihr kommt | you come / you are coming |

| sie/Sie kommen | they/you (formal) come / they/you (formal) are coming |

As you can see, we just removed the ending -en. The part that’s left is called the “stem” of the verb. Now, we can add new endings to the stem: -e for ich, -st for du, -t for er/sie/es, and so on.

Beware: Unlike English, German has a formal version of “you” (Sie – always capitalized) which is used to address people of higher ages, strangers, or people in formal settings like the workplace. “Sie” can be used to talk to one single person or several people at once, and we’re using the same verb form for Sie (you) as for sie (they).

Irregular verbs in German

As in other languages, there are several irregular verbs in German as well. Here, we will have a closer look at the rules for German irregular verbs in present tense.

1. Verbs with a vowel change

Some verbs that have an a or e in their stem change that vowelin the du and er/sie/es forms Let’s have an example for each case: sprechen (to speak) and schlafen (to sleep):

Table of verbs with vowel change

| sprechen: e -> i | schlafen: a -> ä | |

|---|---|---|

| ich | spreche | schlafe |

| du | sprichst | schläfst |

| er/sie/es | spricht | schläft |

| wir | sprechen | schlafen |

| ihr | sprecht | schlaft |

| sie/Sie | sprechen | schlafen |

2. Verbs ending on -sen and -ßen

You will encounter several German verbs with those three letters at the end, and because their stem already ends with “s” or “ß”, they don’t need an additional -s for the du form, which typically ends on -st.. This applies whether there is a vowel change or not:

- essen (to eat) -> du isst (you eat)

- heißen (to be called) -> du heißt (you are called)

3. Regular verbs ending on -den and -ten

If a verb doesn’t have a vowel change in its stem but ends on -den or -ten, we put an extra e between the stem (which is ending on -d or -t) and the regular endings for du, er/sie/es, and ihr. This is what it looks like:

Table of regular verbs ending with -den and -ten

| Pronoun | Arbeiten (to work) | Reden (to talk) |

|---|---|---|

| ich | arbeite | rede |

| du | arbeitest | redest |

| er/sie/es | arbeitet | redet |

| wir | arbeiten | reden |

| ihr | arbeitet | redet |

| sie/Sie | arbeiten | reden |

Now, if a verb ending on -den or -ten also has a vowel change in its stem, the ending of the du form is regular, without an additional e. However, the ihr form keeps the additional e. And only when the stem ends on -t, the er/sie/es forms of those verbs lose their endings altogether. To illustrate, let’s have a look at treten (to step/kick) and raten (to guess):

Treten and raten

| Pronoun | Treten | Raten |

|---|---|---|

| ich | trete | rate |

| du | trittst | rätst |

| er/sie/es | tritt | rät |

| wir | treten | raten |

| ihr | tretet | ratet |

| sie/Sie | treten | raten |

4. Completely irregular

Like every other language, German has a few verbs that need to be memorized individually since they don’t follow the typical conjugation rules – at least not for every grammatical “person”. Three very important and frequent verbs are sein (to be), haben (to have) and werden (to become). They can be used alone, but play a crucial role for the compound tenses as you will see later in this blog.

Table of tenses for sein, haben and werden

| Pronoun | sein (to be) | haben (to have) | werden (to become) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ich | bin | habe | werde |

| du | bist | hast | wirst |

| er/sie/es | ist | hat | wird |

| wir | sind | haben | werden |

| ihr | seid | habt | werdet |

| sie/Sie | sind | haben | werden |

Lots of other very important verbs are irregular, too – for example modal verbs.

Separable German verbs

Separable verbs may be something new to you if you haven’t learned another language with this phenomenon before. But don’t worry, now that you know how to conjugate regular and irregular verbs in German present tense, there is just one additional rule to learn and you will be ready to use them.

There are tons of separable German verbs. Their infinitives (that’s the non-conjugated form you’ll find in the dictionary) look almost like any other regular or irregular verbs, e.g.: ankommen (to arrive), aufmachen (to open), einschlafen (to fall asleep), mitmachen (to participate) and weggehen (to go away). However, you can recognize them by typical prefixes that need to be separated when you conjugate them, for example an-, auf- and ein-: :

- ankommen (to arrive) -> ich komme an (I arrive)

- aufmachen (to open) -> du machst auf (you open)

- einschlafen (to fall asleep) -> er schläft ein (he falls asleep)

Pay attention to the word order as well: If you add more information to a declarative phrase, the separable prefix always moves to the end of the phrase while the conjugated part of the verb remains in the second position:

- Ich komme morgen in Berlin an. (I arrive to Berlin tomorrow.)

- Du machst die Tür auf. (You open the door.)

- Er schläft immer nach der Arbeit ein. (He always falls asleep after work.)

Here is a list of separable prefixes you will notice with a lot of German verbs:

- ab-

- an-

- auf-

- aus-

- bei-

- ein-

- hin-

- her-

- los-

- mit-

- nach-

- vor-

- weg-

- zu-

And some prefixes may be separable or not, for example:

- um-

- umkippen(to fall over) -> Dein Glas kippt gleich um. (Your glass is falling over soon.)

-umziehen (to move house) -> Ich ziehe heute um. (I’m moving house today.)

But: -umarmen (to hug) -> Ich umarme dich. (I give you a hug.)

- über-

überwechseln (to transfer / to change sides)

-> Der Spieler wechselt in eine andere Mannschaft über. (The player is transferring to a different team.)

But: -übersetzen (to translate) -> Ich übersetze einen Brief. (I’m translating a letter.)

German past tenses

Similar to English, there are two different types of German past tenses: Simple Past (Präteritum) and the German Perfect tense with its two versions of Present Perfect (Perfekt) and Past Perfect (Plusquamperfekt). Good news first: Unlike many other languages, the German past tenses don’t make a real difference in meaning. They all express actions in the past. While there is a difference in the meaning in English between “I learned German” and “I have learned German”, you can actually use the German Simple Past as well as the Present Perfect equally. But, it is more of a stylistic difference in German: The Simple Past is generally muchmore formal than the Present Perfect in German. Let’s make it clear by some German past tense examples.

Present perfect: Perfekt

Despite being called “Present Perfect”,this is the most frequently used German past tense. It is used in both, written and spoken German, but definitely the preferred past tense in German conversation. (By the way: If you are planning a trip to a German-speaking country you can also check out our article on how to handle German conversation.

The German Present Perfect consists of two verbs: The conjugated form of haben (to have) or sein (to be) in the Present tense – we call them “auxiliary verbs” in this function –, and the Past Participle, which describes the action and is the “main verb” in this function. Before we explain this in detail, let’s have a look at some examples:

- Ich habe gekocht. (“I have cooked.” / I cooked.)

- Ich habe gelacht. (“I have laughed.” / I laughed.)

- Ich bin gegangen. (“I have gone.” / I went.)

- Ich bin gefahren. (“I have driven.” / I drove.)

The auxiliary verbs haben and sein

Most verbs require the use of haben in German Present Perfect. However, a few very important verbs need to have sein as their auxiliary verb. These include all the verbs of movement, e.g. gehen (to go), laufen (to walk), fahren (to drive/ride/travel), reisen (to travel), but also verbs that mark a change of a state, e.g. aufwachen (to wake up), einschlafen (to fall asleep), sterben (to die), verschwinden (to disappear), passieren (to happen) etc. Weirdly enough, bleiben (to stay) also goes with sein. The two verbs sein (to be)) and werden (to become) are used with sein in Present Perfect as well:

- Movement: Ich bin nach Deutschland gereist. (I traveled to Germany.)

- Change of state: Ich bin eingeschlafen. (I fell asleep.)

- sein: Ich bin im Kino gewesen. (I’ve been to the cinema. / I was at the cinema.)

- bleiben: Ich bin zu Hause geblieben. (I stayed at home.)

- werden: Ich bin krank geworden. (I became sick.)

Past participle

You might have noticed in the examples above that the German participles look similar, but also different to each other. Depending on the verb, building the Past Participle follows these rules:

- Regular Verbs: ge + verb stem + t

- kochen (to cook) -> ge-koch-t (cooked) -> Ich habe gekocht. (I have cooked.)

- lachen (to laugh) -> ge-lach-t (laughed) -> Du hast gelacht. (You have laughed.)

- Verbs ending on -den and -tenrequire the ending -et:

- warten (to wait) -> ge-wart-et -> Er hat gewartet. (He has waited.)

- reden (to talk) -> ge-red-et -> Sie hat geredet. (She has talked.)

- Irregular Verbs: ge + verb stem + en

Beware: Irregular verbs usually have a vowel changein the Past Participle.

- sprechen (to speak) -> ge-sproch-en -> Wir haben gesprochen. (We have spoken.)

- bleiben (to stay) -> ge-blieb-en -> Ihr seid geblieben. (You have stayed.)

- Separable Verbs

Coming back to this type of verb, please pay attention to the place where -ge needs to be in the verb. It always sits between the separable prefix and the stem:

- aufmachen (to open) -> auf-ge-mach-t -> Der Supermarkt hat aufgemacht. (The supermarket has opened.)

- ankommen (to arrive) -> an-ge-komm-en -> Ich bin schon angekommen. (I’ve already arrived.)

- einschlafen (to fall asleep) -> ein-ge-schlaf-en -> Ich bin eingeschlafen. (I have fallen asleep.)

- Verbs with non-separable prefixes

Some verbs have prefixes which are not separable, for example bekommen (to receive), verstehen (to understand), erzählen (to tell) and entscheiden (to decide).

When there is a non-separable prefix, we do not add ge- to create the Past Participle form:

- bekommen -> Du hast ein Geschenk bekommen. (You received a gift.)

- verstehen -> Ich habe es verstanden. (I understood it.)

- erzählen -> Er hat es seiner Mutter erzählt. (He told his mother.)

- entscheiden -> Ich habe mich noch nicht entschieden. (I have not decided yet.)

Verbs with the ending -ieren: The Past Participle forms of these verbs don’t require the prefix ge- and always end on -iert.

- funktionieren (to work) -> Es hat funktioniert (It has worked.)

- studieren (to study at university) -> Ich habe Mathematik studiert. (I took Maths in uni.)

German word order

One important thing to be remembered in German Perfect tense is the sentence structure because the word order is different to many other languages. In a declarative phrase, the auxiliary verb will always have the second position and the Past Participle always the very last position after all the information you want to include in one clause.Let’s look at the following examples:

-

Ich habe letzte Woche jeden Tag von 9:00 Uhr bis 18:00 Uhr gearbeitet. (I worked from 9am to 6pm every day last week.)

-

Ich bin gestern um 22 Uhr eingeschlafen. (Yesterday, I fell asleep at 10pm.)

You don’t always have to start the sentence with the subject. You can also start with a place or time if you want to put special emphasis on this information. In this case, your auxiliary verb (aka the conjugated form of haben or sein) will follow the time or place because the conjugated verb always has to be the second part of any German sentence. The subject then follows the auxiliary verb, and the Past Particle of the main verb goes to the end, as usual:

- Gestern bin ich um 22 Uhr eingeschlafen. (Yesterday, I fell asleep at 10:00pm.)

- Letztes Wochenende habe ich meine Freunde getroffen. (Last weekend I met my friends.)

Now, you are ready to use the German Present Perfect with every verb you want.

Simple past: Präteritum

The German Simple Past (Präteritum) is way more formal and mainly used in written German, for example in literary, academic or administrative texts. Frequent exceptions from this rule include sein (to be) and haben (to have), but let’s take a look at some regular verbs in Präteritum first.

1. Regular German verbs in simple past

To build the Simple Past of regular German verbs, you just have to change their endings:

Remove the -en and add the specific Simple Past ending for each of the grammatical “persons” to the stem of the verb. They are very similar to the regular present tense endings, but contain an additional “t” or “te”. Let’s take a look at kochen (to cook) in Simple Past:

Kochen (to cook) in simple past

| Person | Verb form | Ending |

|---|---|---|

| ich | kochte | -te |

| du | kochtest | -test |

| er/sie/es | kochte | -te |

| wir | kochten | -ten |

| ihr | kochtet | -tet |

| sie/Sie | kochten | -ten |

Did you notice? The forms for ich and er/sie/es both look the same and take the ending -te.

2. Irregular verbs

Irregular verbs change their stem, but most take the same endings as regular verbs would in present tense. Exceptions: The ich and er/sie/es forms don’t have an ending. Let’s take gehen (to go) as an example:

Gehen (to go) endings

| Person | verb form | ending |

|---|---|---|

| ich | ging | - |

| du | gingst | -st |

| er/sie/es | ging | - |

| wir | gingen | -en |

| ihr | gingt | -t |

| sie/Sie | gingen | -en |

Common irregular verbs in German Simple Past are bleiben, fahren, kommen and werden. As werden (to become) slightly differs from the rules we just learned, take a look at its conjugation in Simple Past here:

Conjugation of irregular verbs in simple past

| Person | verb form | ending |

|---|---|---|

| ich | wurde | -e |

| du | wurdest | -est |

| er/sie/es | wurde | -e |

| wir | wurden | -en |

| ihr | wurdet | -t |

| sie/Sie | wurden | -en |

The modal verbs are also irregular in Simple Past and are especially important as they are barely used in Present Perfect.

3. Frequently used verbs in German simple past

As mentioned above, the German Present Perfect is much more common than the Simple Past. However, there are some specific verbs that you should definitely memorize in Simple Past because they don’t often appear in Present Perfect: sein (to be), haben (to have) and geben in the expression es gibt (there is).

Table of verbs sein and haben in simple past

| sein (to be) | haben (to have) | geben | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ich | war | hatte | |

| du | warst | hattest | |

| er/sie/es | war | hatte | es gab (there was) |

| wir | waren | hatten | |

| ihr | wart | hattet | |

| sie/Sie | waren | hatten |

Past perfect

Like in English, the Past Perfect in German is used to express that one action in the past took place before another one.To build the Past Perfect, we conjugate the auxiliary verbs haben or sein in Simple Past and place the Past Participle of the main verb at the end of the clause, as explained in the Present Perfect section above.Basically, we follow the same rules as in Present Perfect tense and only change the tense of the auxiliary verbs:

-

Ich habe gearbeitet. (Present Perfect, I have worked.)

-> Ich hatte gearbeitet. (Past Perfect, I had worked.) -

Ich bin eingeschlafen. (Present Perfect, I have fallen asleep.)

-> Ich war eingeschlafen. (Past Perfect, I had fallen asleep.) -

Ich bin um 20 Uhr eingeschlafen. Vorher hatte ich gearbeitet. (I fell asleep at 8pm. Before that, I had worked.)

In this example, we use the Past Perfect to express that we finished work before we fell asleep. Since the rules for German tenses are not that strict, we could also use Present Perfect for both sentences, and they would still have the same meaning:

- Ich bin um 20 Uhr eingeschlafen. Vorher habe ich gearbeitet.

German future tense: Futur I

As mentioned in the beginning, German natives often use the Simple Present to say that something will happen in the future: Ich koche morgen (I’ll cook tomorrow). However, there is also a specific German Future Tense that is built by combining werden (will) in Present tense with the infinitive form of our main verb (the verb describing the action). Sounds complicated, but actually looks pretty similar to English:

Examples of German phrases in future tense

| German | English |

|---|---|

| ich werde kochen | I will cook |

| du wirst kochen | you will cook |

| er/sie/es wird kochen | he/she/it will cook |

| ihr werdet kochen | you (both/all) will cook |

| sie/Sie werden kochen | they/you (formal) will cook |

Like in Perfect Tense, the German Future Tense requires the second verb to be at the end of a declarative phrase if you want to add several information:

- Ich werde morgen für meine Familie kochen. (I will cook for my family tomorrow.)

- Wir werden nächstes Jahr nach Deutschland reisen. (We will travel to Germany next year.)

Extra hint: The German Future Tense is also used to express assumptions in the present. In this case, you will often find the words wohl or schon which have a similar meaning like “probably” in such expressions:

- Sie wird wohl zu Hause sein. (She is probably home.)

- Er wird das schon wissen. (He probably knows that.)

Future perfect in German: Futur II

With this one, you can express that an action in the future will be completed before another action in the future. Despite being the least common of the German tenses, the Future Perfect is still good to know. As seen in the Futur I tense above, we use a conjugated form of werden as an auxiliary verb. However, we then combine the Past Participle of the main verb with the infinitive form of haben or sein, and move this group to the end of the clause. Seems confusing? Let’s look at some examples:

- Ich werde gekocht haben. (I will have cooked.)

- Ich werde um 19:00 Uhr angekommen sein. (I will have arrived at 7pm.)

The choice between haben or sein depends on the same rules you’ve already learned for the German Perfect tense (see above).

Another important information to keep in mind: In Future Perfect, the Past Participle and the infinitive of haben or sein are inseparable. If you want to add any information to the clause, they move to the end together:

- Ich werde um 20 Uhr schon gekocht haben. (I will already have cooked at 8pm.)

- Ich werde morgen um 20 Uhr schon in Österreich angekommen sein. (I will already have arrived in Austria tomorrow at 8pm.)

German tenses: Recap

So far, we have talked about all important facts about German tenses in the present, past and future, the respective conjugation rules for German regular and irregular verbs, and how German tenses differ from English tenses. As you can see, there are quite a few similarities, which makes it easier to memorize the rules. Now it’s time to practice!

Want to learn German tenses in a fun way?

Try Busuu for free today and get access to online courses in German and a community of native German speakers ready to guide you through all the tenses in German